The booming cannons of the French galleons in the bay below St. Andrews Castle brought John Knox’s first pulpit ministry to a sudden end on July 30, 1547. Though Knox had not participated in the capture of St. Andrews Castle in 1546, he also did not condemn those who had killed the castle’s not so celibate owner, Cardinal David Beaton, who had orchestrated the death of Knox’s mentor George Wishart and several other men who affirmed Martin Luther’s teaching of salvation by grace alone through faith alone. A year after Beaton’s death, Knox decided to make St. Andrews Castle his home and became a tutor, hoping to escape the jurisdiction of the Catholic Church which was intent on arresting protestants.

Though ordained by the Catholic Church to serve as a priest prior to his conversion, Knox only reluctantly agreed to serve as the castle’s preacher after another area pastor publicly charged then the 30-year-old Knox to not “refuse this holy calling .” Though Knox ascended to the pulpit with much trepidation and even a few tears, his first sermons burned with transformational truth. To quote one of Knox’s earlier biographers, “Knox struck at the root of the popery, by boldly pronouncing the Pope to be the antichrist, and the whole system as erroneous and anti-scriptural.” Commenting on his preaching ministry, Knox said, “I will be part of no other church except that which has Jesus Christ as its pastor, which hears His voice, and will not hear a strangers.” Though he preached for only a few months, many of those in and around the castle repented and believed because to quote Knox, “God so assisted his weak soldier, and so blessed his labors.”

Unfortunately for the young reformer and the other 120 defenders of the castle, Catholic France did not take kindly to the murder of Cardinals and sent a fleet to restore order. Once aware that no help would come from England, the leaders of the castle surrendered to the French fleet, expecting to become political exiles. But the French doubled crossed the Scots and made them serve as Galilee slaves.

A Slave

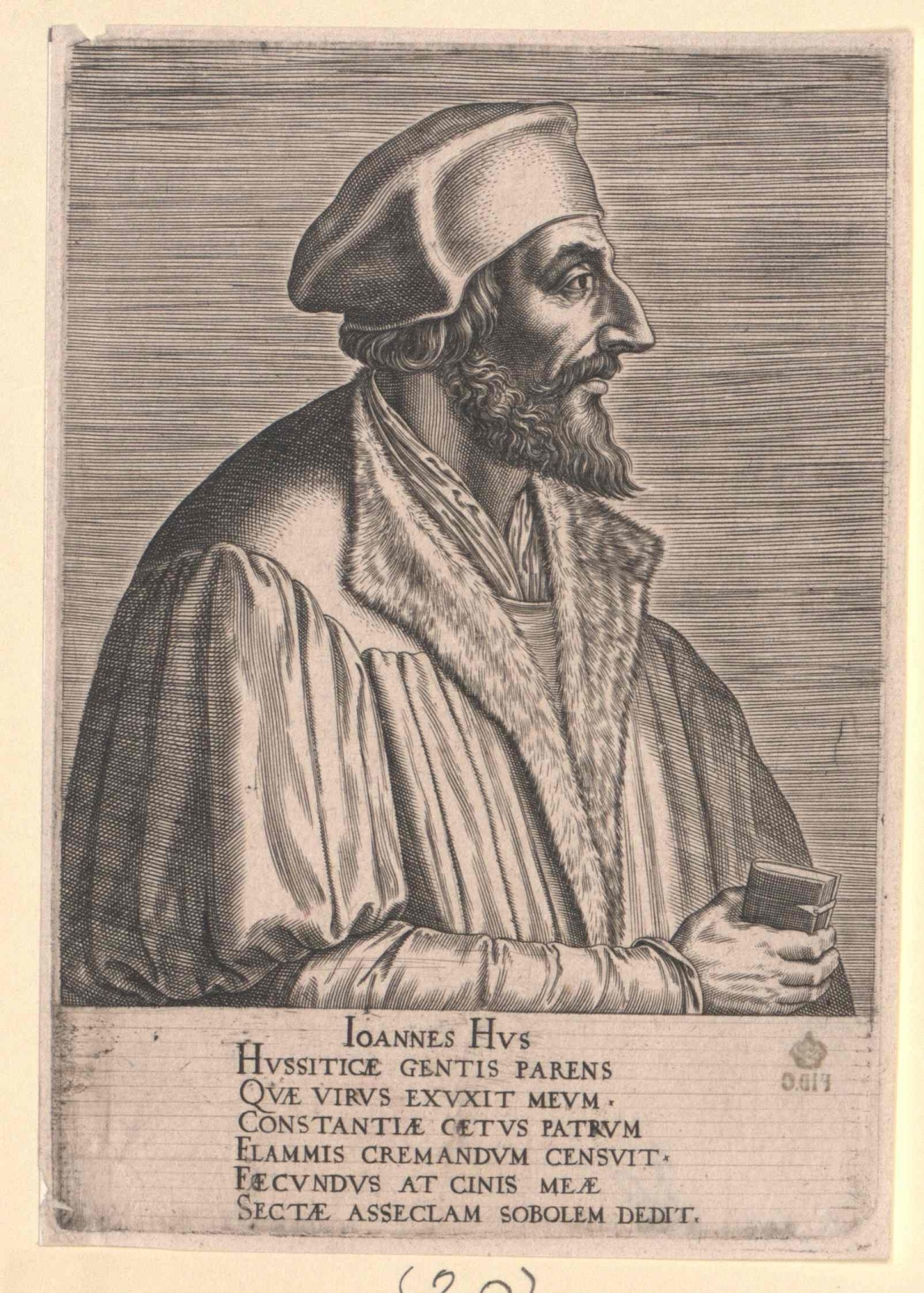

The sickness, exhaustion, and persecution that Knox endured while a galley slave somewhat foreshadowed the general tenure of Knox’s life. Though he preached the same gospel as Huss, Zwingli, and Calvin, the Scotsman would never enjoy the permanence nor the governmental support of those other gospel preachers. He would preach and pastor in the midst of great hardship.

Upon his release from prison in 1549, Knox made his way to England whose king, Edward VI, had embraced the Protestantism of his Father Henry VIII. Though the Anglican church initially embraced Knox, his time in England would prove both contentious and short. He upset his British clergy when he labeled the practice of kneeling before the Lord’s table as “idolatrous.” But more importantly, the young King Edward VI died on July 6, 1553, and his half and devotedly Catholic sister, Queen Mary Tudor, or “Bloody Mary,” ascended to the British throne intent on reestablishing the Roman Catholic faith with both words and the sword.

Fearing for his life, Knox resettled himself and his family in Frankfurt Germany in 1554, hoping to pastor the city’s English congregation. But once again, Knox found himself out of step with his fellow believers over the practice of the Lord’s supper and out of a church. He relocated to Geneva in 1556 to pastor that city’s English congregation.

After spending three formative years pastoring in Geneva and studying under John Calvin who became one of Knox’s closest friend, the reformer attempted a return to England in 1559 only to be redirected to Edinburgh because queen Elizabeth I took exception to Knox’s belief that a “woman in her greatest perfection was made to serve and obey man, not to rule and command him.” At first, Scotland proved equally hostile to Knox. The Bishop of St. Andrews threatened to shoot Knox on sight if the reformer resumed preaching. Undaunted, Knox continued on, revival broke out, and 14 priests in St. Andrews renounced the pope and embraced Jesus as their savior. In 1560 following the death of the Catholic Queen Regent of Scotland, the Scottish parliament ratified the Scottish Confession of Faith which Knox helped write, guaranteeing Protestants the freedom of religion. But even that victory was tainted. A few months later, Marjory (who Calvin labeled as Knox’s “most sweet wife,”) died, leaving Knox to care for his two children.

From 1560-1572, Knox experienced the calmest season of his life during which he wrote several books and became the pastor of St. Giles church in Edinburgh, Scotland. Though Knox enjoyed great success in this pulpit and experienced the joy of marrying his second wife – Margaret Stewart, he still found himself constantly harassed by the youthful and Catholic Queen Mary of Scotland and a handful of others who objected to his unapologetic defense of Protestantism.

On November 9, 1572, Knox preached his last sermon and had to be carried in and out of the pulpit by his friends. Sensing that death was close, Knox exhorted his congregants to stand firm in the faith. In one of his last prayers, he asked the Lord to, “Raise up faithful pastors who will take charge of thy church. Grant us, Lord, perfect hatred of sin, both by the evidences of thy wrath and mercy.” On Monday November 24 around 11PM after spending the day listening to his wife read Calvin’s sermons on Ephesians and John 17, Knox uttered his final words, “Now it is come,” took two more deep breaths, and then died as one historian noted “without out a struggle.” To quote Knox, “Serve the Lord in fear, and death shall not be terrible to you. Nay, blessed shall death be to those who have felt the power of death of the only begotten Son of God.”

A Prophet

Like Luther, Calvin, Wycliffe, and others, Knox unapologetically built his faith and ministry on the Scriptures, believing that God had called him to “instruct the ignorant, comfort the sorrowful, confirm the weak, and rebuke the proud.” He told his fellow Christians in Scotland, “The Word of God is the beginning of life spiritual, without which all flesh is dead in God’s presence; and the lantern to our feet…and…it is the foundation of faith, without which, no man understands the good will of God – so it is the only instrument which God uses to strengthen the weak, to comfort the afflicted, to reduce to mercy by repentance such as have slidden; and finally, to preserve and keep the very soul, in all assaults and temptations.” In other words, the Bible contained the message of salvation, which the Holy Spirit used to open the eyes of the lost and then to sanctify and preserve the saved. As the reformer told Mary Queen of Scotts, “The word of God is plain in itself and if there appears any obscurity in one place the Holy Ghost…explains the same more clearly in other places, so that their can remain no doubt.” As his writings make clear, Knox’s boldness in the pulpit, on paper, and before queens arose from his confidence in the Scriptures that had so changed his life could change the life of those who heard his sermons. To quote Knox, “I desire to communicate with them the light which God hath offered and revealed unto me, in Christ Jesus his Son.”

Knox and the Catholic Church

With his conscience bound to the clear teaching of the Scriptures, Knox found himself frequently at odds with the teaching and practices of the Catholic Church especially the church’s view of the sacraments because Rome had made human tradition equal with Scripture. Knox condemned the practice of the mass because the priestly action of declaring the bread and the wine to be Jesus’ physical body that could impart grace through consumption had no biblical foundation. He wrote, “The Mass is nothing; but the invention of man, set up without…the authority of God’s Word…and therefore is Idolatry.” Knox continued, “For it is not his presence in the bread that can save us, but his presence in our hearts through faith in his blood which has washed out our sins, and pacified his Father’s wrath toward us.” Similarly, Knox sought to correct the Catholic Church’s understanding of baptism, noting that it too was a sign and not a means of regeneration. Holy water saved no one. To quote Knox, “No man is so regenerated, but…he has need of the means which Jesus Christ…appointed to be used in his church, to wit, the Word truly preached, and the sacraments rightly administered.” Captive to the Word of God, Knox called the Catholic Church to return to the clear teaching and practice of the Scriptures.

Knox and Politics

Given the political turmoil of his age and the church’s dependence upon the state, Knox also believed that the state should be shaped by the Bible. As he said in one of his sermons, “Kings then have not an absolute power to do in their regiment what pleases them; but their power is limited by God’s Word.” Moreover, Knox believed that the state’s very survival depended upon its obedience to the Scriptures. If kings or queens openly rebelled against God’s Word, then God would in time crush those nations as he had crushed Israel for its rebellion against God. Knox warned the English government saying, “The Lord will in his own time destroy unjust governments by his own people, to whom he will supply proper qualifications for this purpose, as he formerly did with Jerubbaal.” According to Knox even rulers and citizens who did not actively sin but only passively endured false teaching stood in danger of God’s judgment. Knox proclaimed, “For God does not only punish the chief offenders, but with them, does he condemn the consenters to iniquity.” Pushing further than Calvin, Knox instructed his followers to obey their kings and queens only as long as they followed Christ. He wrote, “we must not obey the king of magistrate when their commands are opposed to God and his lawful worship; but rather…expose our person and lives, and fortunes to danger.” He wanted the Scriptures to shape by the individual, the church, and state.

Knox and Queen Mary

Acting out his convictions, Knox preached against Queen Mary’s attempts to reinstate the mass and advance Catholicism in Scotland. The queen disliked Knox’s sermons and ordered him to appear before her on five different occasions to give an account for his actions. During the first confrontation, the queen accused Knox of treason because he taught a religion other than the one practice by the crown. Knox rejoined, “Madam, as right Religion took neither original strength nor authority from worldly Princess, but from the Eternal God alone, so subjects are not bound to frame their Religion according to the appetites of their Princes.” The reformer then noted that his aim was not rebellion but that “both Princes and subjects obey God.” Undaunted by the queen’s first summons, Knox continued to boldly preach against the queen’s embrace of the errors and abuses of the papacy.

As anticipated, Knox found himself back at court in December 1562 and then again in April 1563. His most famous interaction with the queen occurred a month later in May1563. At that meeting, the queen shed a “great abundance” of tears because Knox opposed her wedding to her Catholic fiancé. Knox replied, “I never delight in the weeping of any of God’s creature, yes, I can scarcely well abide the tears of my twin boys…much less rejoice in your majesty’s weeping.” Still, the reformer refused to abandon his convictions and continued to preach the full counseling of God’s Word, embracing whatever consequences might come. In October 1563, the queen once again summoned Knox to court and then referred him to the privy council for punishment. Nothing would come of that inquiry as the queen’s administration became increasingly unstable because she indulged in an affair. By God’s grace, Knox would be vindicated for his faithfulness to the Scriptures. As the reformer told his friends, “For never shall we find the church humbled under the hands of tyrants, and cruelly tormented by them, but therewith, we shall find God’s just vengeance to fall upon the cruel persecutors, and his merciful deliverance to be showed to the afflicted.”

Two Rough Edges to Knox’s Preaching

While the crux of Knox’s confidence in the Scriptures proved commendable, it’s jagged edges proved unhelpful. On occasion, the Reformer attacked secondary issues within the church with the same force that he used against the false teachers outside of Protestantism. For example, he so vehemently criticized Thomas Crammer’s British liturgical teaching that the Lord’s Supper should be consumed while kneeling that churches in England and then in Frankfurt removed him from their pulpits. Moreover, these conflicts proved fruitless. Knox’s tactics failed to win men to his position. Calvin, one of Knox’s closet allies, offered Knox the following caution: “It behooves us to strive sedulously that the mysteries of God be not polluted by the admixture of ludicrous or disgusting rites. But with this exception, you are well aware that certain things should be tolerated even if you do not quite approve of them.” Knox forever struggled with this exception.

Similarly, Knox’s poor hermeneutic – specifically his method of interpreting and applying the Old Testament (OT) – led Knox at times to be offensive where the Scriptures were not. Knox viewed the OT prophets more through epistolary than a historical or prophetical lens which led him to proclaim that earthly sufferings were the direct result of individual or national sin. He declared that “The prophets are the interpreters of the Law and they make the plagues common to all offenders.” Commenting on how God used Isaiah, Jerimiah, and Ezkiel to call down judgement on Moab, Egypt, and other nations, Knox proclaimed, “the plagues spoken of in the law of God, appertain to every rebellious people, be they Jews or be they Gentile, Christians in title or Turks in profession.” Using the OT to justify his speculation into the secret judgements of God, Knox told the Catholic Queen Regent of Scotland that the tragic death of her two sons within the space of six hours was a sign of “the anger and hot displeasure of God” and called her to repent. Though Knox rightfully called sinners to repentance, the Scriptures did not provide him with a mandate to apply the judgements of the OT to his day. If anything, Knox would have done well to heed Jesus’s teaching in John 9:1-12 were he declared that physical illness was not always a direct result of sin. “It was not that this man sinned, or his parents, but that the works of God might be displayed in him (Jn 9:3).”

A Pastor

The only thing that equaled Knox’s passion for preaching was his love for the saints who had heard his preaching. Knox devoted much of his writing ministry to encouraging the fainthearted, longing to assist them in their sanctification.

Knox and His Letters

As Knox moved from place to place, he kept up a steady correspondence with his mother-in-law, Elizabeth Bowes. He readily encouraged her through her many bouts with depression. He wrote to her of Jesus saying, “he did taste the cup of God’s wrath against sin, not only to make full satisfaction for his chosen people, but also, that he might learn to be pitiful to such as are tempted…therefore, despair not, for your troubles be infallible signs of your election in Christ’s blood, being ingrafted in his body.” Knox writings reveal that he faithfully reverenced Mrs. Boews as his, “Dear beloved Sister” for as long as she lived.

He also kept in touch with his congregations in England and Scotland, encouraging them to stand firm in the face of persecution. As Queen Mary Tudor began arresting and killing protestants such as Thomas Crammer, Knox encouraged his former congregations to hold fast to the gospel. He reminded them that, “By avoiding idolatry you may fall into the hands of earthly tyrants, but obeyers, consenters, and maintainers of idolatry, shall not escape the hands of the living God. For avoiding idolatry, your children shall be deprived of father, friends, riches, and earthly rest; but by obedience to idolatry, they shall be left without God, without knowledge of his Word, and without hope of his kingdom.” He then pointed them to God’s faithfulness proclaiming, “the Lord himself will be your comfort; he shall come in your defense with his mighty power; he shall give you victory when none is hoped for, he shall turn your tears into everlasting joy.” As he said in another letter, “This is the chief and principal cause of my comfort and consolation in these most tearful days, neither can our infirmities nor our daily persecutions hinder the return of Jesus Christ to us.”

Knox also frequently addressed Scottish Christians. He penned his first letters to the saints of St. Andrew’s while a galley slave. He remained in contact with the Scottish church while on the continent, encouraging them to form biblical churches that installed biblically qualified men to preach. He wrote, “Wheresoever God’s Word hath supreme authority, where Jesus Christ is affirmed, preached, and received to be the only Savior of the world, where his sacraments are truly administered, and finally, where his Word rules…there is the true church of Jesus Christ.” He also repeatedly called his fellow Scotsmen to take the threat of false doctrine seriously, encouraging political leaders to affirm the biblical teaching of the reformation and their subjects to hold said rulers to the commands of Scripture. To quote Knox, “Sleep not in sin, for vengeance is prepared against all the disobedient.” He forever pointed his congregants to the grace, mercy, and hope of Jesus.

Knox and His Prayers

In addition to encouraging his fellow Christians, Knox also faithfully prayed for his family, friends, and his opponents. Knox promised his mother-in-law that, “I will daily pray that your fears may be relieved, and [that your] doubts may obtain the same, to the glory of God and your comfort everlasting.” Similarly, he told his fellow English believers, “My daily prayer is for the sore afflicted in those quarters…beseeching God of his infinite mercy to so strengthen you; that in the weakest vessels Christ’s power may appear.” He also prayed for his adversaries asking the Lord, to “Illuminate the heart of our sovereign lady, Queen Marry.” At other times, he prayers for his enemies proved less encouraging. Once, he asked the Lord to “Pour forth thy vengeance upon” those who persecuted and murdered Christians. Knox’s prayers proved so effective that the Queen regent of Scotland once remarked that she was “more afraid of [Knox’s prayers than an army of 10,000 men.”

Knox’s confidence in the power and promises of prayer arose from his confidence in God’s sovereignty. Like Calvin, Knox affirmed that God predestined men and women to salvation through election in accordance with his holy will. The reformer wrote, “There is no way more proper to build and establish faith, then we hear and…believe that our election…consists not in ourselves but in the eternal and immutable good pleasure of God.” According to Knox, what proved true of salvation proved true of all of life. Knox noted, “the way of man is not in his own power, but…his foot-steps are directed by the Eternal.” Resting in God’s power, Knox expectantly prayed for the advancement of the gospel and the destruction of the wicked because God’s Word had decreed that the battle between good and evil would culminate in the return and triumph of Christ. Commenting on the importance of prayer, Knox said, “Let no man think himself unworthy to call and pray to God because he has grievously offended his majesty in times past…To mitigate or ease the sorrows of our wounded conscience, two plasters hath our most prudent Physician provided, to give us encouragement to pray…a Precept and a Promise. The precept … “Ask, and it shall be given unto you.” …[the] promise… “If ye, being wicked, can give good gifts to your children, much more my heavenly Father shall give the Holy Ghost to them that ask him (Matt. 7).” …let us be encouraged to ask whatever the goodness of God hath freely promised.” Knox’s faith drove him to prayer for those whom he loved.

Knox’s Pastoral Misstep

As with his preaching, Knox’s pastoral skills also proved imperfect. At times, the urge to care for his congregants led Knox to rashly put pen to paper. Most infamously, he secretly published the The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women in 1558 as Mary Tudor sought to hand over England to the rule of Philip I, the Catholic king of Spain. Unfortunately for Knox, Mary died on November 17, 1558, ending all hopes of England becoming Catholic. Mary’s protestant, half-sister Elizabeth I ascended to the throne on January 15, 1559. Though Knox had the Catholic monarch in view, Elizabeth I still found the content of his book offensive. To understand why, one only has to Knox’s first sentence which unfolded as follows: “To promote a Woman to bear rule, superiority, dominion, or empire above any Realm, Nation, or city is repugnant to Nature; contemptable to God, a thing most contrary to his revealed will and approved ordinances; and finally, it is the subversion of good Order, of all etiquette and justice.” Though Knox did not think all women incapable of ruling, citing the example of Deborah, the damage had been done. He would never again live in England. Sadly, he also inadvertently blunted Calvin’s influence in England. Though Calvin knew nothing of the book’s publication until after it began to circulate and disagreed with parts of its premise, Elizabeth I forever held Calvin responsible for its publication as it had been birthed in Calvin’s Geneva.

Conclusion

Knox died confident in his faith. But his legacy has proved less than certain. Though Knox’s first biographers viewed him favorably, and an increasing number of historians have begun to portray the reformer as a Philistine prone to insults, sexism, and cultural conservatism. Acting on these views, the church where Knox is buried has turned the reformer’s grave into a parking space.

Without question Knox possessed faults worthy of criticism. At times, he violated the boundaries of biblical truth that he so prized. Failing to heed the warnings of Calvin and others, Knox turned secondary debates within the protestant church into first tier issues that thereby disrupted the unity of the local churches he served. He also misapplied the prophetic texts of the OT, drawing harsh unwarranted conclusions that went against the teaching of the New Testament. Even his pastoral ministry at points proved rushed and ill-timed, stunting the spread of the Calvinism in England.

But much of the historical critique of Knox focuses not on Knox’s biblical transgressions but rather on his devotion to the Bible. Such criticism proves neither new nor novel. Commenting on the rumors that swirled around him during the 1500s, Knox once quipped, “if all [the] reports were true, I would be unworthy to live in the earth.”

But the reports then as now were not true. Overall, Knox proves worthy not of repudiation but of imitation for he built his life and ministry around the unfettered preaching of the gospel. He witnessed to peasants and queens alike. And like his savior, Knox’s boldness in the pulpit was matched by his tender care for the weak and weary. Though he traveled much and suffered even more, Knox always found time to pray for and write to those congregations and individuals who had sat under his preaching. He possessed the two voices that Calvin deemed essential for pastoral ministry. The reformer could both gather the sheep and drive away wolves. If anything, the church needs more men like John Knox who could care less about their grave being turned into a parking lot as long as the gospel they loved marched on. May we never forget the line attributed to Knox that, “One with God is always in the majority.”

On Oct 31, 1517, the monk, Martin Luther turned the world upside down with a few shift taps on the door of the Wittenberg Chapel. Luther hoped his 95 Theses, 95 concerns, about the state of the Catholic Church would lead the church to reexamine her doctrine of indulgences, pieces of paper that promised forgiveness from sin in exchange for a fee. Luther wrote,

On Oct 31, 1517, the monk, Martin Luther turned the world upside down with a few shift taps on the door of the Wittenberg Chapel. Luther hoped his 95 Theses, 95 concerns, about the state of the Catholic Church would lead the church to reexamine her doctrine of indulgences, pieces of paper that promised forgiveness from sin in exchange for a fee. Luther wrote, Men and women could only secure the blessing of salvation when

Men and women could only secure the blessing of salvation when  And suffer, Huss did. Instead of receiving a hearing for his beliefs, Huss was imprisoned a few days after he arrived in Constance. When Huss was brought before the Council, the Council shouted down Huss’s voice down with a veracity that reminded Huss of how the Pharisees treated Christ as his trial. The leaders of the church allowed Huss to answer

And suffer, Huss did. Instead of receiving a hearing for his beliefs, Huss was imprisoned a few days after he arrived in Constance. When Huss was brought before the Council, the Council shouted down Huss’s voice down with a veracity that reminded Huss of how the Pharisees treated Christ as his trial. The leaders of the church allowed Huss to answer