In an odd twist of fate, Zwingli became famous for something that he never did. Catholic leaders in the Swiss Canton of Zurich which Zwingli called home, accused him of eating pork sausages on March 9, 1522. Though Zwingli was with Christoph Froschauer and the other ten men who ate the pork meat, Zwingli never took a bite himself. As he told his accusers, “I had nowhere taught that Lent ought not to be kept, though I could wish that it were not proscribed so imperiously.” Though he did not inhale any sausage, Zwingli had still managed to ignite the Swiss reformation. Biographer Bruce Gordon concluded, “It did not matter whether Zwingli ate the sausages or not; he was fully complicit, encouraging the breaking of the Lenten fast.” To understand why eating sausages proved to be so monumental and why Zwingli encouraged the little meal, we must travel backwards in time to 1484, the year of Zwingli’s birth.

The Preacher

Huldrych Zwingli came from a stable and well-off family. His father served as the mayor of his hometown of Wildhaus, an alpine village in the Toggenburg Valley. Zwingli’s uncle served as the head of a Swiss Abbey. With their blessing, Zwingli commenced his academic studies in the city of Bern at the age of ten. Twelve years later in 1506, Zwingli graduated from the University of Basel with a Master of Art’s degree. Though he had spent his youth studying philosophy, Zwingli still felt unsettled after graduation, turned to the Catholic Church for answers, and became a priest in the city of Glarus. While the more rural setting of Glarus provided the inquisitive Zwingli with the time needed to begin his theological education, the posting would not last. In 1515, the leaders of Glarus took exception to Zwingli’s vocal disapproval of the Swiss mercenary practice because the city had just signed a treaty with Francis I of France which stated Glarus would fill the French ranks with Swiss troops. Thus, nine years after entering the church, Zwingli found himself moving to the Einsiedeln parish.

Conversion and the Gospel

While Zwingli’s three year stay in Einsiedeln would prove to be his shortest posting, it would also prove to be his most formative. Here, Zwingli encountered the gospel of Jesus Christ and broke with Catholic Church doctrine which championed tradition and justification by faith and works. While Zwingli never recounted his full conversion story, he did credit the Scriptures for his spiritual transformation. He wrote, “I learned the purport of the Gospel from reading the treaties of John and of Augustine and from the diligent study of Paul’s epistles in the Greek.”

While he spoke sparingly about his conversion, he possessed no reticence when discussing God’s saving work. He wrote, “This is the gospel, that sins are remitted in the name of Christ; and no heart ever received tidings more glad.” Repudiating the Catholic idea that “justification by works” was “especially necessary, Zwingli said, “If we could have won salvation by our own works or our own innocence, He [Jesus] would have died in vain.” Zwingli affirmed that salvation came by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone. He wrote, “The true religion of Christ, then, consists in this: that the wretched man despairs of himself and rests all his thought and confidence on God.” As the Reformer noted elsewhere, “Righteousness or guiltlessness according to the law is not because of any human deed, but through Christ alone whose own sinlessness purged our guilt before God so that if we cling to him…he shall be our innocence and righteousness before God.”

When Zwingli came to Zurich on January 1, 1519 at the age of 35 to assume the role of the people’s priest, he came to do one thing: preach the word. He wrote, “no one can set at rest the conscience as well as the word of God.”

The Reformer

Having come to faith through his study of the Scriptures, Zwingli decided to devote his first years in Zurich to preaching expository sermons from the gospel of Matthew, hoping to expose his audience to Jesus’s saving grace.

But Zwingli did not think God’s grace would end at conversion. He wrote, “When, therefore, the Son of God has once freed us from the death of sin and we firmly believe this, we cannot help being transformed by a wonderful metamorphosis into other men.” In other words, the Swiss reformer believed the Spirit who illuminated and saved the lost would also sanctify and purify those whom he had saved. Zwingli continued, “whoever does not change this life from day to day, after he has been redeemed in Christ mocks the name of Christ and disparages and disdains it before the unbelievers.”

The Reformation Begins

After hearing Zwingli’s sermons for a little over a year, small groups of Zwingli’s new converts began to openly practice what Zwingli had preached. And where did they strike first? They ate sausages, seeking to live out Zwingli’s conviction that salvation came through faith alone as opposed to human works. In so doing, they declared that the bishops and popes who had proscribed fasts as a matter of faith had in Zwingli’s words, “sinned greatly.”

What began at a kitchen table quickly enveloped the whole social order of Zurich. Before 1522 ended, Christians in Zurich had started to call for churches to remove their statues and altars, for monasteries to be disbanded, for the education system to be reformed, for the mass to be abolished, for the end of unjust taxation or tithes, and for the end of priestly celibacy. As Zwingli told his followers, “We shall try everything by the touchstone of the Gospel and by the fire of Paul. And when we find things in harmony with the Gospel we shall keep them, when we find things thus not in harmony, we shall throw them out.” In the short, the gospel invaded every aspect of Zurich’s public life with a speed that not even Zwingli could control.

The reformer often lamented that he had to send books filled with half-baked ideas to the publisher because the next crisis was upon him. Zwingli said of his most famous work Commentary on True and False Religion, “I have been so hurried along, that I have often hardly had a chance to reread what I have written much less to correct or embellish it.”

But while Zwingli welcomed the speed at which things happened, Bishop Hugo who resided in Constance about 50 miles south of Zurich found Zwingli’s spreading influence to be a great annoyance. In 1522, he began to censor priests who embraced the reformers ideas.

A Disputation and More Reforms

Facing a dilemma over who to follow, the government of Zurich held a disputation between Zwingli and representatives from the bishop of Constance on January 29, 1523. The intense debate lasted only a morning because the council believed it wise to break for lunch. When the council returned a few hours later with full stomachs, they declared Zwingli the winner and commanded the village priest to preach sermons from the Scriptures alone. In so doing the council both institutionalized Zwingli’s movement and confirmed the Catholic’s belief that Zwingli was the “arch-heretic.”

Now backed by Zurich’s government, Zwingli’s reforms moved forward with greater speed. From 1523 – 1525, the city installed a new liturgy, allowed for priest to stop offering the mass, and began celebrating the Lord’s Supper as a memorial. Responding to overzealous mobs, the city established a commission in 1524 that closed churches for a few days to facilitate the peaceful removal of icons and altars. By 1525, Zwingli had convinced the Zurich government to fully disband the city’s various monastic orders and to repurpose their properties as hospitals and homeless shelters. He also reformed the city’s education system, redirecting state funds to support preaching ministries and those who trained preachers in the original languages and the art of sermon crafting. Shortly before his Zwingli’s death, Zurich would also publish a German translation of the Scriptures which had been begun at the outset of Zwingli’s time in Zurich.

During this time, Zwingli also got married first secretly and then publicly in 1524. Two years later, he helped Zurich create the Court of Domestic Relations. It sought to encourage godly behavior and to issue marriage licenses which Zwingli believed to be in great need because the vows of celibacy taken by the city’s priest, monks and nuns produced in Zwingli’s words “prostitutes” and “bastards.” Zwingli believed such vows proved detrimental to the clergy and society because Paul’s command that “everyone” should be married did, “not exclude priests or any other persons” from the joy of marriage.” He went on to note that, “Any bishops who forbid priests to marry are false and impious and sacrilegious…because the Church once ordered that a bishop should be the husband of one wife according to the deliverance of Paul to Timothy and Titus.”

Opposition Grows

But as his reforms spread so did the opposition to his cause. First, a small group of his own followers called the Anabaptists split from Zwingli in 1525. Led by Balthasar Hubmaier, the Anabaptists affirmed that only adult believers should be sprinkled with the waters of baptism and called for Christians to embrace pacifism. Zwingli said of Anabaptist’s doctrine, it “all boils down to rebaptism…that one should not have a magistrate, that one should hold all things in common and that one owes neither rest nor tithes.” In 1526, Zurich held a disputation to discuss the merits of the Anabaptists’ theology. Again, Zwingli won the day. The Anabaptist who did not recant were exiled or imprisoned. In 1527, Zurich even executed an Anabaptist named Manz. Though Zwingli was not involved in Manz’s trial, Zwingli also did not object to the death sentence, believing Anabaptists to be more of civic menace than a theological one. Having already dodged one revolt over taxes and tithes, Zwingli responded harshly to what he perceived to be the Anabaptists’ call for anarchy, “the destruction of the government.”

Second, Zwingli butted heads with Luther over the practice of the mass. Like Luther, Zwingli rejected the Catholic idea that the eating of the bread and the drinking of the wine found at the Lord’s table contained the physical body of Christ and thereby once consumed both cleansed the Christian soul and enabled it to further resist sin. Zwingli wrote, “It is therefore, false religion which taught that the use of the symbolic bread destroys sins; for Christ alone destroys sin by his death.”

But while clear on what it was not, Zwingli and Luther could not agree on what it was. Luther believed in consubstantiation which declared that Christ was still present in the bread spiritually and thereby blessed the believer who ate the sacrament in faith. Zwingli said of Luther, “you maintain that the flesh is…eaten for the justification of the soul and to bestow strength and the rest.” The Swiss Reformer held to the memorial view which declared that “the eating of the Eucharist does not take away sins but is the symbol of those who firmly believe that sin was exhausted and destroyed by the death of Christ and give thanks therefore.” Though Zwingli and Luther met in 1529 and exchanged a good number of books and tracts seeking to find common ground, the two men found themselves increasingly at odds with each other believing the other had grossly distorted the Scriptures. When asked about Zwingli’s eternal destiny, Luther said, “I wish from my heart Zwingli could be saved, but I fear the contrary; for Christ has said that those who deny him shall be dammed.” While Zwingli never doubted Luther’s salvation believing their discussion to be over nonessentials of the faith, he did denounce Luther’s arguments as “being badly reasoned and so sluggish” and wished that they had never been published. The men would never be reconciled. Zwingli said of their relationship, “we are fighting about symbols so cruelly that love has to stand very far away.”

Lastly, the Catholic Church continued to write against and condemn Zwingli’s actions. On May 19, 1526, Bishop Hugo held a disputation at Baden that contained representatives from all the Swiss states that met for three weeks. Led by the Catholic polemicists Van Eck who had called Luther to recant in 1519, this disputation sided against Zwingli and decreed that his writings should be banned. Though Zurich never caved to the pressure of the other states or Rome, Zwingli’s life remained under threat. His opponents regularly used graffiti on public buildings and bridges to insult and attack Zwingli. Rocks were thrown through his windows. On another occasion, men hatched a plot to assassinate Zwingli, asking him to come visit a dying man so that they could murder the reformer when he got to the home. Thankfully, Zwingli’s servant discerned the messenger’s intent and kept Zwingli from going. Commenting on the situation, his first biographer and friend Myconius wrote, “he was almost always escorted, without being aware of it, by good citizens, lest evil should befall him on the way. And the Senate in this perilous time placed watchers around his house at night.”

The Politician

Zwingli proved to be one of the most politically charged personalities of the reformation though he never held public office. He even taught that pastors should not be politicians writing, “those who have the staff, that is, worldly power along with the office of shepherd, are not shepherds but wolves.” Despite this strong belief, Zwingli still possessed a large amount of influence over Zurich’s political culture, serving on several committees that drafted legislation and corresponding with other national leaders and kings.

The First Kappel War

With Zurich having embrace biblical preaching by 1527, Zwingli increasingly turned his political sights outward, seeking to both spread the gospel and to protect Zurich from attack. By 1529, the Christian Fortress Law which served as a Protestant mutual defense pact had come to include the cities of Zurich, Constance, Bern, St. Gallen, Basel, Schaffhausen, Biel and Mullhausen. Feeling threatened, the Catholic Swiss states signed a mutual defense treaty with Austria. Within months of the second treaty being signed, the Catholic city of Schwyz executed Jacob Kaiser for advocating for Zwingli’s reforms.

Horrified by this abuse of power, Zwingli called Zurich to declare war on Schwyz. The council voted down his proposal which also came with a battle plan because the other protestant states objected to the war. Humiliated, Zwingli offered his resignation, which two friends eventually convinced him to withdraw.

After securing the tepid support of Bern, Zurich declared war on Schwyz and marched on the city on June 8, 1529. But when the vastly superior Protestant forces encountered the Catholic army, the Bernese troops refused to take the field with their Zurich brothers. Instead, the Bernese commanders negotiated a peace treaty with the Catholics. Again, Zwingli’s hopes for a protestant Switzerland were dashed. The First Kappel Peace Treaty demanded only that the Catholic states dissolve their treaty with Austria and that each state be given the freedom to choose between Protestantism or Catholicism.

The Second Kappel War

Then in 1531, the Medici’s of Italy conducted a brief war that encompassed some Swiss territory. While the Protestant states mobilized to protect Swiss sovereignty, the Catholic states did nothing. Freshly convinced that Catholicism needed to be rooted out of Switzerland, Zwingli again called for Zurich to go to War. Again, the city council and Bern rejected his call to arms. Preferring diplomacy, they set up a land blockade of the Catholic states in May 1531. But the Catholic states thwarted the blockade and gained additional military strength. Sensing their failure, Zurich declared war on the Catholic states on October 9, 1531. Though Zwingli tepidly advised against going to war at this point and threatened not to march with the army to which he had been elected to serve as a chaplain, he once again changed course and marched out with the poorly trained troops.

Lacking strategy, arms, and good intelligence, the Zurich troops suffered a total defeat on October 11, 1531. When the Zurich troops encountered the Catholic army, the Zurich general did not know if he should advance or retreat. Eventually, he decided to retreat and inadvertently led his 3,000 man army into a bog which enabled the Catholic force of some 7,000 men to decimate the broken ranks of the Zurich troops in less than an hour. When the battle ended, a 100 Catholics had been lost compared to 500 Zurichers, one of whom was Zwingli. While the fog of war has prevented historians from knowing the exact nature of his death, most believe Zwingli was stabbed multiple times. As he breathed his last, he managed these words, “What evil is there in this? They are able, it is true to kill the body but not the soul.”

Stunned by their defeat and by Zwingli’s death, Zurich sued for peace with its Catholic neighbors. It abolished the Fortress Law pact, relinquished all plans for protestant expansion, and granted several of its contested territories the freedom to once again practice Catholicism. Though defeated, most of Zwingli’s religious reforms remained in force. And with the help of Heinrich Bullinger who served as the next preacher of Zurich, the city would continue to maintain its fidelity to the Scriptures and its Reformation heritage that Zwingli had gifted it for years to come.

Zwingli’s Legacy

Of all the characters who spawned, shaped, and guided the Reformation, Zwingli proves to be one of the most complex. He championed the Scriptures and built his life and his movement upon faithful, expository preaching. He possessed the ingenuity and the energy needed to transform a city in twelve years. But he also possessed an unhelpful bent towards pragmatism that led him to live in a secret marriage, to surrender the control of the Zurich church to its secular government, and to engage Luther, the Anabaptists and others with a speed and forcefulness that often proved offensive and counterproductive. Moreover, Zwingli earned the unique distinction of being the only protestant reformer to have died in battle, a lasting testimony to his involvement in secular politics, an involvement Bullinger, his immediate successor, repudiated as unhelpful. Bullinger refused to serve on Zurich’s various committees throughout his pastoral tenure in Zurich.

Final Thoughts

What do we make of the passionate, gifted, and yet flawed father of the Swiss reformation? We praise him for his fidelity to Scripture and for his belief that Scripture could be understood through prayer and study. And we praise him for his faithful exposition of Scripture which saved thousands and shaped Bullinger and Bucer who discipled Calvin whose doctrine of the Lord’s Supper continues to be practice in most protestant churches. As Bullinger noted, “Zwingli lives, however, just as Scripture speaks of Abel, though dead, still being alive. He remains in his faith and his writings.” After all, who else has accomplished so much through the simple eating of sausages?

But at the same time, we can also honestly acknowledge his failures, noting that sometimes he moved too quickly and too polemically, allowing pragmatic concerns to influence the application of our theology. As Bruce Gordon noted, “He was neither a hero nor martyr. We must see him for what he was – an embattled prophet.” May the lessons of this Swiss Reformer and prophet not be lost on us.

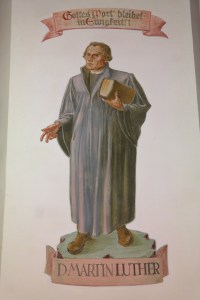

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther set off an earth quake that would reorder Christendom with a few taps of a hammer and with a postage stamp. Luther did not believe that his 95 thesis which first appeared on the door of the Wittenberg Chapel and that were mailed to Cardinal Albrecht of Mainz were controversial. Rather he saw his document as reforming abuses of Catholic doctrine. A few months earlier while delivering his

On October 31, 1517, Martin Luther set off an earth quake that would reorder Christendom with a few taps of a hammer and with a postage stamp. Luther did not believe that his 95 thesis which first appeared on the door of the Wittenberg Chapel and that were mailed to Cardinal Albrecht of Mainz were controversial. Rather he saw his document as reforming abuses of Catholic doctrine. A few months earlier while delivering his  On July 17, 1505, Luther entered the Augustinian Monastery in Erfurt much to his father’s dismay. Luther had been destined for a career in Law. But on July 2, 1505, he had been caught in a severe thunderstorm. As thundered boomed overhead and as lightening flashed about him, Luther promised St. Anne that he would take monastic vows and devote his life to the church if he survived. Luther made it out alive. And so, he began serving the Catholic Church, happily embracing her doctrine of salvation by grace and works.

On July 17, 1505, Luther entered the Augustinian Monastery in Erfurt much to his father’s dismay. Luther had been destined for a career in Law. But on July 2, 1505, he had been caught in a severe thunderstorm. As thundered boomed overhead and as lightening flashed about him, Luther promised St. Anne that he would take monastic vows and devote his life to the church if he survived. Luther made it out alive. And so, he began serving the Catholic Church, happily embracing her doctrine of salvation by grace and works.