By 1532, both the British government and its church had universally panned William Tyndale’s books. King Henry VIII (of six wives fame) had sent spies into Europe to kidnap Tyndale and return him to London. The bishop of that same city, Cuthbert Tunstall, had denounced the books in a sermon and then tossed them into a massive bonfire. And, Thomas More – a priest and close advisor to Henry VIII- had published a confrontational and large (80,000 word) critique of Tyndale’s works. In that mammoth volume, More captured the mood of the nation’s leaders when he labeled Tyndale as “mad,” “devilish,” and “a heretic.” The Catholic priest then warned his readers that Tyndale’s books possessed the power to turn, “true Christian folk into false, wicked wretches.”

Ironically, Tyndale’s books proved so distasteful because they championed the content and authority of the Scriptures. Tyndale believed that God’s Word in conjunction with the Holy Spirit was sufficient to save sinners, build the church, and sanctify the saints. To quote Tyndale, “We trust not in this friar or that monk, neither in anything, save the word of God only.” Operating on this believe, Tyndale sacrificed his comfort, career, and even his life to “cause every boy that drives the plough to know more of the Scriptures than the pope does!”

Salvation, Education, & Exile

Like Martin Luther who started the Reformation in 1517 with the posting of his 95 Theses, Tyndale did not begin his career with revolution in mind. Tyndale’s sharpest critic conceded the reformer had begun his career as “a man of right good living… studious and well learned in Scripture… and in divers places in England [he] was very well liked and did great good with preaching.”

Tyndale was born around 1495 into a Cotswold family on the border of Wales that had made its fortune in textiles. After leaving home, Tyndale earned a bachelor’s degree from Oxford in 1512 and then a master’s degree in 1514. During this season, he was also ordained as a Catholic priest. He then transferred to Cambridge in 1516 before retiring from academia to serve as the tutor to Sir John Walsh’s two young sons. Seemingly, he left Cambridge in 1522 to have more time to translate books such as Erasmus’s Enchiridion which offered a critic of disorderly priests and noblemen.

Not long after transitioning to the Walsh’s home in Sodbury, Tyndale was accused of preaching heresy and found himself before of a tribunal of bishops. Tyndale wrote of that experience: “The chancellor…threatened me grievously, and reviled me, and rated me as though I had been a dog.” But nothing more would come of the charges because the priests that had accused Tyndale would testify against the reformer.

Though the contents of Tyndale’s sermons have been lost, the incident points to a change in Tyndale’s faith. By 1522, Tyndale had become well acquainted with the Scriptures, had repented of his sins, and had embraced the doctrines of grace as taught by Luther. Tyndale believed that God used the law to show men and women their “sin and unrighteousness” so that with the help of the Holy Spirit they would embrace the gospel through faith. Echoing Luther’s view of Romans, Tyndale wrote: “A man is justified by faith only… And when I say that faith justifies, understand thereby, that faith and trust in the truth of God and in the mercy promised us for Christ’s sake, and for his…works only, quiets the conscience and certifies…that our sins are forgiven, and [that] we have part in the favor of God.” Or as Tyndale said more succinctly elsewhere, “except a man have knowledge of his sins, and repent of them, he can have no part in Christ.”

Scholars debate Tyndale’s path into the reformation, pointing to the influence of men such as Erasmus, Luther, and John Wycliffe who had translated the Bible into English from Latin about a hundred years before Tyndale was born. Though Tyndale interacted with Erasmus, was steeped in Luther’s writings, and was well acquainted with Wycliffe’s life, ministry and his translation of the Bible, neither Tyndale nor any of his contemporaries documented the author’s transition into the protestant faith. But the realities of his faith were unmistakable.

Convinced that, “the Scripture is the light and life of God’s elect, and that mighty power by which God creates them,” Tyndale decided to spend his life translating the Scriptures into English. In his notes to his translation of the Pentateuch, Tyndale said that he had been moved to Translate the New Testament because he believed that lay people would only understand the truth of the gospel if “the Scripture were plainly laid before their eyes in their mother-tongue, that they might see the process, order, and meaning of the text.” As Tyndale explained elsewhere, “That precious thing which must be in the heart…is the word of God which…through the preaching of gospel, proffers, and brings unto that all that repent and believe, the favor of God in Christ.”

Such ideas proved revolutionary because the English church possessed little gospel preaching and even fewer copies of the Bible. What little preaching and gospel translations that did exist were mostly in Latin which few English people understood. Tyndale lamented, “Is it not a shame that we Christians come so often to church in vain, when he who is fourscore years old knows no more than he that was born yesterday?”

Understanding that he needed more protection than the Walsh’s could provide if he were to translate the New Testament into English, Tyndale sought the support of the Bishop of London. But Tunstall had little interest in Tyndale’s work and refused to add the reformer to his staff. Understanding now that “not only was there no room in my Lord London’s palace to translate the New Testament but also that there was no place to do it in all of England,” Tyndale sailed to Hamburg, Germany in May 1524. He would never return to England.

The Church, the Scriptures, & Persecution

But he did print his first translation of the New Testament into English in 1525. Almost as soon as the Bible were printed, England put pressure on the German states to arrest their rogue theologian, forcing Tyndale to flee to the city of Worms for protection. Here in 1526, Tyndale embarked upon his most productive era that began with his publication of his second edition of his New Testament. It would not end until his arrest in 1535. Over the next eight years as he traveled about Europe, Tyndale produced multiple editions of the New Testament, translated several Old Testament books, and wrote several theological works such as the Parable of the Wicked Mammon and Against Prelates.

With each successive publication, the opposition to Tyndale grew. Almost as soon as his New Testaments arrived in England, Bishop Tunstall and others began burning the books. About this time, Tunstall purchased several thousand of Tyndale’s New Testaments intending to keep the Bible out of the hands of the common people. But the purchase produced the opposite effect. Tunstall’s funds enabled Tyndale to pay his debts and to secure the printing his second edition of his New Testament. This edition meet with even greater success and became the first widely read English translation of the Scriptures because it contained, “clear, everyday, spoken English.”

Tyndale had anticipated such persecution knowing that “preaching that is a salting…stirs up persecution,” and had managed to stay a step ahead of Tunstall, Cardinal Wolsey, and others. But between 1531-1534, the Catholic Church managed to locate and execute at least seven of Tyndale’s supporters and sympathizers.

In 1529, More also began launching print attacks against Tyndale that placed the reformer on the defensive. Though More complained that Tyndale’s books contained “the worst heresies picked out of Luther’s works,” (things such as Luther’s criticism of purgatory, celibacy, and the pope) More’s most damaging attack which still circulates concerned the quality of Tyndale’s translation. More proclaimed that “the translation of Tyndale was too bad to be mended.” Thus, into the fire it went.

But what More objected to was not sloppy work or a changing of the Greek manuscripts as More had done to support the Catholic view of verbal tradition. Rather, More objected to Tyndale’s work in the Greek and Hebrew manuscripts which led the reformer to place the authority of the Greek and Hebrew text above the authority of popes and councils. To quote Tyndale, “When I have read the Scripture, and find not their doctrine there…I do not give so great credence unto their doctrine as unto the Scripture.”

Following this maximum, Tyndale departed from the Catholic understanding of ekklesia as “church.” Tyndale translated the word as “congregation,” believing that all believers (and not just the priests and bishops) were to be the salt and light that Jesus spoke of in Matthew 5:14-15. Tyndale also translated the Greek word as presbyteros as elder instead of bishop.

These changes which better reflected the Greek text had profound implications for the church. Since the church was “begotten through the word,” then the Scriptures and not the pope would be the church’s final authority. Tyndale noted, “God’s truth depends not on man. It is not true, because man…admit it to be true, but man is true, because he believes it.” Since the Scriptures were the final authority, then local congregations could appoint elders and preachers “to preach God’s word purely, and neither to add or diminish it.” To quote Tyndale, “Let God’s word try every man’s doctrine, and whomsoever God’s word proves unclean let him be taken for a leper.” If someone had leprosy, Tyndale believed the local church could “rebuke” and even remove that man from the pulpit. Tyndale concluded, “No man may yet be a common preacher, save that he is called and chosen…by the common ordinance of the congregation.”

This belief was further bolstered by Tyndale’s Understanding the keys of the kingdom in Matthew 16:19. The reformer said that this text was no more the exclusive domain of the apostle Peter and of popes than the command that Jesus gave to Peter in Matthew 18:21-22 to forgive others seventy times seven. Tyndale located the power to receive people into the church and to excommunicate them from the church in the local congregation. Tyndale wrote, “every man and woman, that knows Christ and his doctrine have the keys, and the power to bind and loose.”

In other words, More took issue with Tyndale’s translations not because they contained errors but because they removed errors that had propped up the Catholic Church’s tradition of papal authority and its resulting belief that sinners could “be justified by the works of the ceremonies and sacraments, and so forth.” For Tyndale, the Scriptures alone were sufficient to save and to build the church.

Sanctification, A Royal Divorce, & Death

When seeking to guide Christians through the complexities of the secular world, Tyndale once again appealed to the authority of the Scriptures. He encouraged wives to heed the example of Sarah and the words of Paul and to submit to their husbands. Similarly, he encouraged husbands to love their wives: “God has made the men stronger than the women; not to rage upon them…but to help them…and win them unto Christ, and overcome them with kindness, that out of love they may obey the ordinance that God has made between man and wife.” Tyndale also encouraged children to obey parents. He called Christians to love their neighbors and enemies, graciously meeting the needs of others without asking for loans or forms of repayment.

In response to the German peasants revolt of 1524, which was said to have resulted from Luther’s theology, Tyndale encouraged his readers to entrust their souls and wellbeing to Jesus. He encouraged kings to submit to the Scriptures and to “oppress not your subjects with rent, fines or custom…to maintain your lusts, but be loving and kind to them, as Christ was to you.” If the king became a tyrant, Tyndale told the citizens to put their “trust in God, then God will deliver you out of their tyranny for his truth’s sake.” If God delayed in rescuing his people, the citizens had no right to revolt. If they did, “then they make way for a more cruel nation.” God alone would judge kings. Tyndale believed the Scriptures could establish and maintain a just society.

Tyndale’s ethical writings caught the attention of Henry VIII with mixed results. At first, they angered British monarch. When Henry VIII sought to divorce his first wife, Catherine of Aragon – his brother’s widow, Tyndale naively entered the conversation in 1530, hoping to bring the scriptural clarity to the dilemma that the Catholic Church lacked. After surveying several Old Testament texts that dealt with divorce, Tyndale declared in The Practice of Prelates that Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine was “lawful.” Unfortunately for Tyndale, Henry who disregard the reformer’s arguments having already determined to end his marriage to Catherine. Later English printings of The Practice of Prelates overseen by Queen Elizabeth I, Henry VIII’s daughter, would omit the reformer’s section on marriage and divorce.

Tyndale possessed some awareness of the king’s sentiments and rejected all of Henry VIII’s invitations to return to England. He told the kings’ messengers that “he [Tyndale] will not promise to stop writing books, or return to England, until the King will grant a vernacular Bible.” As Henry VIII sought to finalize his divorce in 1533, an unknown person in the king’s government recruited the frivolous nobleman Henry Philips to locate Tyndale.

While Philips searched for Tyndale, Henry VIII’s new wife, Anne Boleyn, introduced Tyndale’s earlier work The Obedience of the Christian Man to her husband. Though Henry VIII’s appreciation of the book remains debated, Anne who was both a supporter of Tyndale and of his translations managed to warm Henry VIII to the reformation. But by that time, Philips had already found and befriended Tyndale.

Philips’ duplicitous actions highlight Tyndale’s one notable fault: the reformer’s failure to discern between friend and foe. Though Tyndale’s patron, Thomas Pointz, distrusted Philips, Tyndale brushed Pointz’s concerns aside and welcomed Philips into his inner circle. Tyndale had made a similar error in 1525 when he sought Bishop’s Tunstall’s support. He committed the same mistake a year later when he partnered with William Roye only to discover that Roye lacked the expertise in Greek in Hebrew that Tyndale valued. The one thing Roye most excelled at was insulting his opponents of whom he had many. After a year of working together, Tyndale ended his relationship with Roye. Unfortunately, Tyndale would not get the same opportunity with Philips.

On the evening of May 21, 1535, Philips led Tyndale down a dark alley surrounded by troops who quickly arrested the reformer and transported him to Vilvorde castle. Once Tyndale’s friends learned of his arrest, they asked Henry VIII to intercede on the reformer’s behalf. Showing his change of heart, Henry VIII allowed his diplomats to work for Tyndale’s release through back channels. But when he learned of Tyndale’s coming transfer, Philips acted. He accused Henry VIII’s envoy of being complicit in Tyndale’s crimes. Consequently, the man set to safely transport Tyndale to England found himself having to escape Antwerp under the cover of darkness. Tyndale’s fate was sealed.

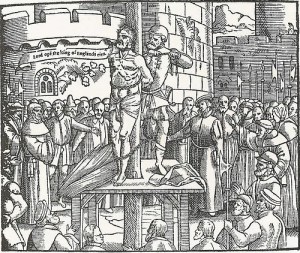

In the early days of October 1536, Tyndale found himself tied to a stake awaiting his death. With his last breaths, Tyndale cried out, “Lord! Open the king of England’s Eyes.” The executioner then pulled the rope around Tyndale’s throat tight and brought the reformer’s life to an end. The executioner then set fire to the bundles of wood stacked around the reformer’s lifeless body, reducing it to an ashy dust.

In August of 1536, Tyndale’s tribunal condemned the reformer to death for the crime of heresy. Unfortunately, historians know little about the tribunal’s proceedings or of Tyndale’s thoughts while in captivity. All that remains from that era is one letter in which Tyndale asks to be granted the freedom to read the Hebrew Bible and new clothes.

Conclusion

Though Tyndale fell victim to the flames of persecution, his mission to see the Bible read in the common language of his people would not end. In the very New Testament that had led to Tyndale’s death, Jesus had promised that “until heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the Law until all is accomplished (Matt 5:18).” In 1539, Henry VIII’s eyes did partially open. That year, the king placed a copy of the Great Bible which was based on Tyndale’s translations of the Old and New Testament in every church of England. God’s word had triumphed over the gates of hell.

Tyndale’s influence did not end with the reformation. Scholars estimate that around 84% of the King James Bible reflects the wording of Tyndale’s Bible. Tyndale also shaped the Jerusalem Bible which is the Catholic Church’s translation of the Scriptures into English. In other words, the English world has the Scriptures today in its various translations because Tyndale sacrificed everything, including his life so that we might have access to the gospel that save sinners. May we forever follow Tyndale’s example and in-turn “seek nothing but the truth and to walk in the light.”